Note values: the basic building blocks of rhythm

When it comes to Grade 1 music theory, one of the first things we’re asked to learn are note values - the basic building blocks of rhythm. These are the symbols in written music that show us how long a note should be held or played.

Like my blog How to Read Music: The First Three Landmark Notes, I’m going to break this down slowly. These are the fundamental building blocks after all, and understanding them will lay the foundation for everything that follows.

The ABRSM’s Grade 1 Music Theory syllabus includes the note values of semibreve, minim, crotchet, quaver and semiquaver (or ‘whole note’, ‘half note’ etc. - more on this below), and their equivalent rests, as well as tied notes and single dotted notes.

So let’s start at the beginning.

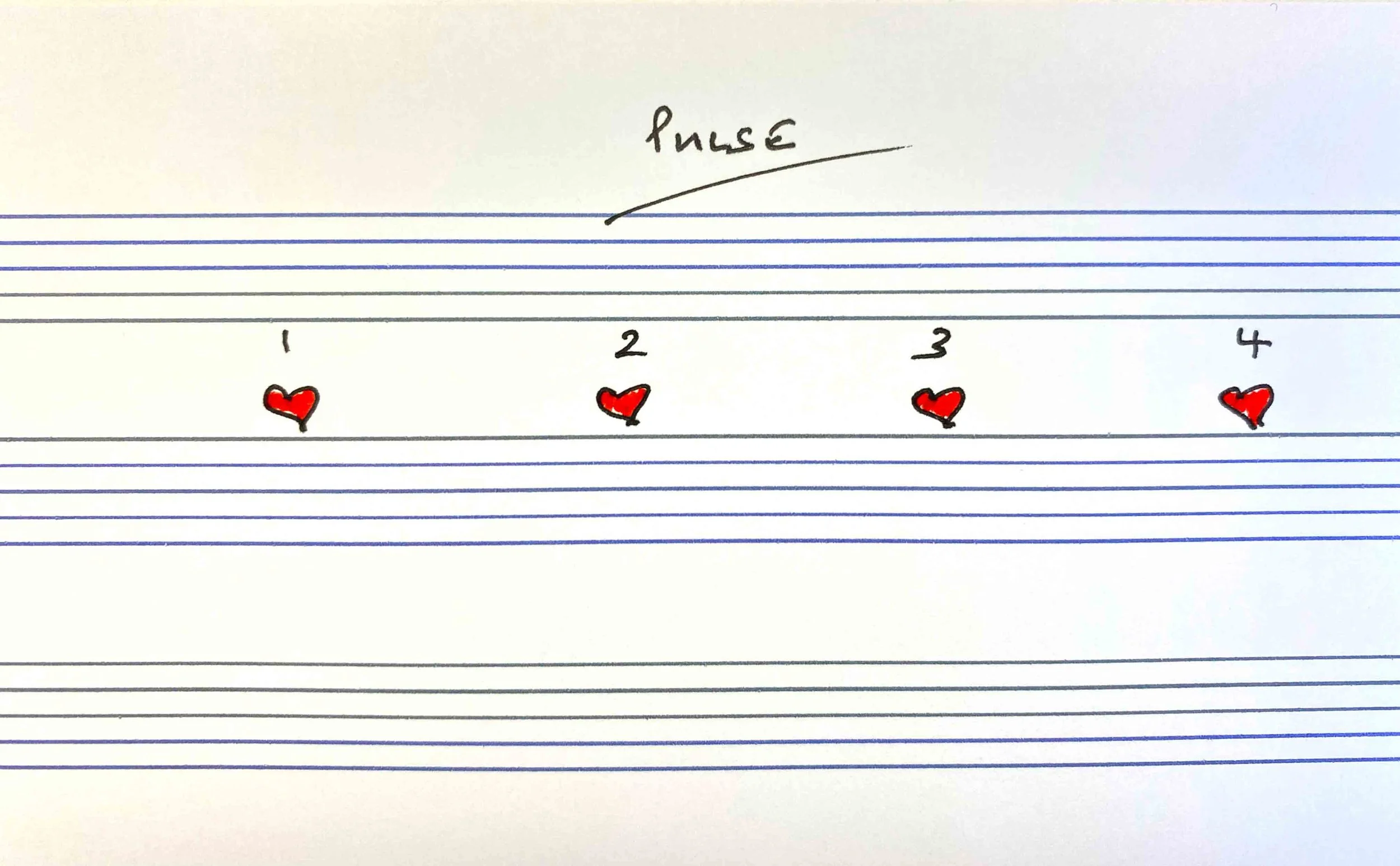

Pulse or beat

The way that I make sense of note values is by thinking about the idea of pulse, the steady, regular beat in music, like a musical heartbeat. In other words, what we naturally tap our feet to when we listen to a song, for example, 1, 2, 3, 4.

Try listening to this version of Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D, for example, and you can hear the same steady four-beat pulse repeating all the way through.

Note values

Once we understand the pulse or beat in a piece of music, note values tell us how long to hold a note for in relation to that pulse, or beat. In ABRSM Grade 1 music theory, we need to learn five note values.

Semibreve

The semibreve (or ‘whole note’) lasts for four pulses, or four beats.

Minim

The minim (or ‘half note’) lasts for two beats.

Crotchet

The crotchet (or ‘quarter note’) lasts for one beat.

Quaver

The quaver (or ‘eighth note’) lasts for half a beat, so you can fit two of them into one beat.

Semiquaver

The semi-quaver (or ‘sixteenth note’) lasts for a quarter of a beat, so you can fit four of them into one beat.

Understanding how these notes relate to the beat is what turns counting into rhythm.

A quick note on American and British names

In America, note names are based on fractions. A whole note is the longest, and every other note is named by how much of that whole it takes up. So a half note lasts half as long, a quarter note lasts a quarter, an eighth note lasts an eighth, and so on.

Our UK names come from older European music traditions. Words like crotchet (meaning “little hook”) and quaver (meaning “to shake”) were first used hundreds of years ago to describe how the notes looked or sounded.

So, let’s lay each of these notes under the pulse, so we can see how many pulses, or beats, each note lasts for.

How counting out loud can help us understand rhythm

Counting out loud can help us to see this as we can hear and feel how long each note lasts in real time. When we say the rhythm, using words like “1-and, 2-and” and “1-e-&-a”, it helps us to map where each note sits inside the beat.

Here’s how that sounds for our five notes:

Semibreve (whole note) – lasts 4 beats

You hold the sound through four beats. You only say the first beat, then count the rest silently.

Count:

“1… 2… 3… 4…” (one sound held for all four beats)

Imagine clapping once, then holding your hands together through beats 2, 3, and 4.

Minim (half note) – lasts 2 beats

Each minim fills two beats, so there are two in a 4-beat bar.

Count:

“1… 2, 1… 2”

You clap (or play) once on beat 1 with each note held for two beats.

Crotchet (quarter note) – lasts 1 beat

Each beat gets one note, this is the “pulse” of most music.

Count:

“1, 2, 3, 4”

You clap evenly with the beat, one clap per number.

Quaver (eighth note) – lasts half a beat

Each beat is divided into two equal parts: the beat and the off-beat.

Count:

“1-and, 2-and, 3-and, 4-and”

You clap on both the number and the “and”. This is how you keep two even sounds inside each beat.

Tip: The “and” is exactly halfway between the beats- that’s what makes your rhythm feel steady.

Semiquaver (sixteenth note) – lasts a quarter of a beat

Each beat is divided into four tiny, equal parts.

Count:

“1-e-&-a, 2-e-&-a, 3-e-&-a, 4-e-&-a”

You clap four times for every beat, quick but steady.

Tip: Begin with a slow beat so you can practice placing each smaller sound evenly between the main beats.

Once we can count these rhythms confidently, dotted notes, ties and rests will start to make much more sense as they all fit into this same time structure.

Three simple rhythm exercises to practice note values

Here’s a few short exercises to help make things stick:

Listen and tap: play Pachelbel’s Canon in D and tap along with a steady “1, 2, 3, 4.” Notice how all the rhythms fit neatly inside that pulse.

Clap each note value: semibreve, minim, crotchet, quaver, semiquaver in order, keeping a steady beat. Count out loud as you go.

Mix and match: write or clap a few 4-beat bars using different combinations of note values, but always making sure they add up to four beats.

Key takeaway

Everything in rhythm comes back to pulse. Once we understand how each note value fits inside the beat, we’re not just reading symbols, we’re learning to feel time in music.

About the listening suggestion

Johann Pachelbel – Canon and Gigue for Three Violins and Continuo in D Major: Canon

Performed by the Orchestre de chambre Jean-François Paillard, conducted by Jean-François Paillard.

From Pachelbel: Canon – Albinoni: Adagio – Bach, Bonporti, Molter: Works (Warner Classics / Erato, 1984; remastered 2019).